'Sensational Trial at the Congleton Police Court:

A Minister's Alleged Libel on the WAAC'

In 1918, Richard H Quick, Primitive Methodist Minister at Congleton, was fined £40 for asking questions about the conduct of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. He was prosecuted under the ‘Defence of the Realm Act’, which was introduced as a War Time Measure in 1915.

A Woman’s Place

The case highlights conflicting attitudes towards women, and their changing role during the First World War. Recognising the work of women in the ammunition factories, people began to ask whether women could actually be used in the army. They might even be used in France.

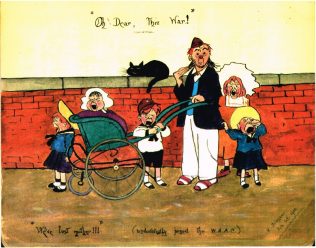

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was formed in July 1917. Despite a rigorous selection process, far more women applied to join the WAAC than had been expected. It caused strong feeling on both sides. As the illustration from this autograph album shows, many felt that a woman’s place was in the home and she should stay there.

What the WAAC are doing

At the time of the trial, the WAAC had been in existence for about 8 months, and was growing both in numbers, and the variety of work they did. They were all volunteers, and their contribution was increasingly recognised as indispensable, because as the war dragged on, every woman who joined the WAAC released a man to fight at the front. Thousands of women were in France, taking over cooking, cleaning, motor transport, clerical work, and many other tasks. The Congleton Chronicle reported: ‘The war could not go on without them’. The message from the War Office was that only England has been able to organise women in this way, and all sorts of measures have been put in place ‘to shelter and protect’ them, so that they are safer than if they had been at home. This was an important propaganda designed to increase recruitment.

Purity and Truth

Richard Quick, as a representative of the church, was concerned about immorality, which some saw as the inevitable result of having men and women in close proximity, especially when women were not under the ‘protection’ of parents or guardians.

On 6 February 1918, the day that Mrs Atlee, Secretary of the Purity League, was to address a meeting of girls in Congleton on matters of social morality, he received worrying news from ‘a friend’. So he went to the meeting and as Mrs Atlee was about to speak he handed her a letter.

“I received news from a friend yesterday, who is a soldier, with some 10,000 others stationed in Yorkshire. Opposite their lines are the lines of the WAAC, and he expressed that the type of life lived between the two lines is appalling. Is the League aware that there is a Government Order in relation to the WAAC, one of whose Clauses is as follows: ‘If any of these girls give birth to a child, and the girl is single, the Government will pay the girl £16 and take custody of the child and keeps the same.’ This, to my mind, is putting a premium on a horrible vice, and preparing for such an immoral state of society tomorrow which should make all right-minded people zealous to oppose. Will you let me know if anything of the nature I have mentioned has come under your notice, and whether the Vigilance Committee has the matter under attention.”

A Foul Lie

When later questioned in court, Quick maintained that he was purely motivated by a desire to establish the truth. However, he faced the serious accusation of spreading false reports and making false statements, liable to cause damage to the war effort.

The prosecution maintained no such Government Order existed, and the rumours from Yorkshire were completely unfounded. It was suggested that the rumours could have been started by men who felt that their places were being taken by women. Richard Quick felt the full weight of the law because rumours like this, about the morality of women in the WAAC, were dangerous. The government knew they stopped women joining the service, at a time when they were vital to the war effort. As the local newspaper reported, ‘Anything that tends to prejudice its recruiting must be stamped out.’

Report of the Trial

The Congleton Chronicle filled three columns with the report of the trial, showing the great interest it aroused. ‘The Congleton Borough Police Court was crowded on Monday, when the Rev R H Quick, Primitive Methodist Minister, Congleton, and residing at Bourne Villa, Park Lane, appeared in answer to two summonses charging him with spreading false reports, and also with making false statements on the 6th February 1918. The case aroused considerable interest, not only locally, but throughout the country, and many who had journeyed a distance to be present at the hearing were unable to obtain admission to the Court. Several of the ladies officially connected with the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps were present in Court.’ The letter he had handed to Mrs Atlee was said to be ‘of an exceedingly dangerous character at the present crisis of the war.’

Richard Quick – Villain or Victim?

It is difficult not to feel some sympathy for Richard Quick. His defence was that, having just received the disturbing news of immoral happenings in Yorkshire, he wrote the letter to Mrs Atlee because he thought she might be able to tell him if it was true or not. However, it is sad to reflect that the church was more concerned about protecting women’s morals than recognising their abilities and achievements.

After being found guilty, and fined £40 (which had to be paid in a week), Richard Quick wrote this poem. It reveals, perhaps, an attitude to women that might seem a little unwise in the circumstances!

Sweet Dora is a pretty lass,

Especially when you please her,

But if you’re apt to ruffle her

She’ll prove a perfect teaser.

Should you just say the thing that please

She will with joy abound

But if you do the damsel tease

‘Twill cost you forty pounds.

The Victim

Sources

The Congleton Chronicle, 1918

Manuscript poem shown by his son to John Anderson

Comments about this page

Further evidence on the trial of Rev R H Quick

The report in the local newspaper gives a rather dim view of Rev Quick, so I was fascinated when a researcher at Englesea Brook came across a letter in the PM Leader which supports the view he was more a ‘victim’ than a ‘villain’. Henry Williamson (not a Primitive Methodist himself) says that there was no suggestion that Richard Quick’s letter had done any harm, or that he was acting from any unworthy motive. The puzzle seems to be why Mrs Atlee made it public. Her ‘lack of discretion and ordinary common sense in her handling of his letter entirely passes comprehension.’ In his view it was an unfair trial, whose object was to act as a warning to others. Mr Quick had done all he could to co-operate and apologise, and the level of the fine was outrageous. Magistrates usually have some regard for a person’s ability to pay, and in this case a fine of £5 or £10 might have been the maximum expected. As a Primitive Methodist minister, there was no way he could pay this out of his own pocket. It was the colliers of Mow Cop who rallied to Mr Quick’s support. One of them, a young man who was in court during the hearing, gave £5 to help him. Others had to be restrained from giving more than they could afford! They succeeded in raising enough to pay the fine, but as Henry Williamson pointed out, this meant that the effect was to punish innocent people. One local Anglican described the penalty as ‘wicked’ and ‘damnable’, and another remarked, ‘If ministers are not to make enquiry about such matters, who ought?’ If nothing else, it seems that this case united local Christians in their moral indignation, but perhaps did little to advance the cause of women’s rights.

(Source: ‘Prosecution of Rev R H Quick’, Letter from Henry Williamson, Swan-bank, Congleton, in The Primitive Methodist Leader, 25 April 1918, p 243)

Add a comment about this page