Cambridge: Primitive Methodism in Cambridge

Transcription of Article in the Christian Messenger by Shirley Windram

Despite the geographies, which are apt to be so literal, there are really two Cambridges beside the Cam. There is the Cambridge of the colleges, polite, well-bred, full of colour and life, and devoted equally perhaps to sport and learning, and there is the other given up to trade, with streets, some of which are as drab and monotonous as any elsewhere. The old feud between “Town” and “Gown” is happily extinct, but the distinction between the two survives, and in outlook and atmosphere they are quite unlike – a fact to be recognised by any church which would retain its under-graduates.

It was of course among the townsfolk that Primitive Methodism started. Joseph Reynolds was the pioneer. In August, 1821, he found his way from distant Tunstall, and the account of his privations reads like a transcript from the diary of some primitive apostle It is impossible to give a consecutive narrative of the early days, but in March, 1824, Cambridge appears as a branch of the Nottingham

Circuit, and it is interesting to note that in midsummer of the same year, William Clowes and John Nelson visited the town for the purpose of re-opening the chapel which had been enlarged by the addition of a gallery.

Of no less interest is the story which appears to connect the Rev. Charles Simeon, the famous evangelical leader, and the spiritual father of Henry Martyn, with our church‘s struggles. “There was in Cambridge,” says‘ Simeon‘s biographer, “a certain enthusiastic Nonconformist labourer named Johnny Stittle, a kind of well-meaning, self-constituted city missionary in the viler parts of Cambridge, and called by the undergraduates a ‘Ranter.‘ He used to hold his meetings in a room, and when the attendance grew too large for one room, he threw down the partitions and used the whole floor of the house; and again enlarged his improvised chapel by taking in also the upper storey, cutting out the central part of the bedroom floor, but leaving enough to make a wide gallery all round, upheld by pillars. As he was but a day-labourer, it was understood that Mr. Simeon aided him in the expense of these alterations.” Commenting on this in the Connexional History, Mr. Kendall remarks: “In this extract the ‘self-constituted city missionary’ has given him the same reproachful name our fathers bore; nor, indeed, do we know of any other denomination, besides our own, that, before 1836 – the year of Simeon’s death – would have made room for John Stittle and his methods.” It is pleasant to think that the early doings of our church had the approval of so great a man as Mr. Simeon and that he was ready to help work, however informal, which made for the common weal.

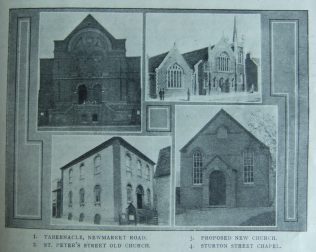

Primitive Methodism to-day is represented in the university town by three churches. Till recently there was a fourth in Panton Street. The latter, though, in a back street, and over-shadowed by prominent neighbours, did not appeal to the eye of modern Cambridge. Its latter history was one of steady decline, and after various attempts to revive the cause, the building came to be sold. The proceeds, £625 net, went to form the nucleus of the Forward Movement. So that out of defeat it is hoped that good will yet come.

Of existing places, the least in point of size is that in Sturton Street, a populous street in a working class locality. Accommodating only one hundred and fifty hearers, it has nearly fifty members, a flourishing Sunday school and other prosperous institutions, and enjoys a degree of success out of proportion to its bulk. In general enthusiasm and evangelistic zeal this church is like a bit of northern Methodism. From time to time conversions take place, and even college professors from more formal gatherings have appreciated leading its worship. Started in 1875, it meets a felt need in the neighbourhood. It is to be hoped that before long convenient premises will be erected that it may properly, garner where it has gleaned.

The largest chapel is the Tabernacle. It was built in 1876 at a cost, including several cottages, of £3,390, and took the place of one of blessed memories in Fitzroy Street, the scene of some of the most notable happenings in local Methodism. The present building stands fairly prominently on the Newmarket Road, seats five hundred and fifty people, and is in many respects fitted to serve the district round it. A small band of workers have stood by it loyally. Unfortunately, its history has been checkered, and in addition, it is burdened by a large debt. Within the last two years this latter has been slightly reduced. It now stands a little below £700. The Tabernacle was the head of the Cambridge Second Circuit until three years ago, when the two Circuits were amalgamated. A great need is better school premises.

The immediate hope of our church and the point of strategical importance is in St. Peter’s Street. It is close to the colleges and near town and suburbs. It is also in a working-class district and adjacent to two main thoroughfares. A cause has been in the locality from the commencement, and at the present time our strongest society is found there. In spite of disabilities, there are encouraging features. In one way and another, many young people are attached to the place, and the Band of Hope, a crowded institution, worked with unflagging zeal, is by far the largest in the town, and contributes fully half the numbers of the annual town procession.

The structure, however, is quite unequal to modern needs. With a cellar-school, without a vestry, without even a class room, unless two tiny shuttered spaces can be so called, and in a building on which the total outlay fifty years ago was only £954 our church is attempting to retain its young and strengthen its hold amid all the well-equipped buildings and architectural splendours of present-day Cambridge! It is magnificent, but it is not war.

Recognising this, the society is now preparing for a new venture. More than two years ago property was bought which stands back to back with the present premises and fronts the main road. On this thoroughfare it is intended soon to put up a structure which will be a credit to the Connexion and a useful centre for the work. As regards aspect, the situation is ideal. Standing on a slight hill, the proposed tower will be easily seen. The road is the main Cambridge artery. Certainly in future, the church will not suffer from being out of sight and out of mind. The church itself is to seat between four and five hundred people and the schools to accommodate about four hundred scholars. The outlay, inclusive of site, fixed provisionally at £5,000. It is expected to lay the stones in 1913

Good premises, of course, cannot ensure success – the art of the building is no substitute for the spirit of the founders – but, all things being equal – they go a long way towards it. It is intended to fill the pulpit with the picked men of Methodism, men who know the atmosphere of a university town, and it is hoped that the church will eventually become a tower of strength.

Though the local need is great, it was with an eye to even larger interests that the matter was first set on foot. With its famous colleges, Cambridge, of course, is a great educational centre. Men come up to it from near and far. And it was felt that an effort should be made to retain the distinctively Methodist contingent whose loyalty is apt to be strained by the many unsettling influences of a University.

It is to be feared that the case for our undergraduates is not understood. To touch the University generally is not, of course, contemplated. Our own men also are not yet numerous, though certainly there are more than many think. But with a deep sense of the value even of few – a single Oxford man, Professor Peake, has left his impress on the whole of Methodism – with the knowledge that scholarships multiplying, they will increase, and knowing their isolation amid novel influences in a strange town, our leaders felt it was only the right thing to provide for them a worthy spiritual home. And surely this is Christianity and common sense.

Much more might be said. Some time ago the writer was looking through a list of graduates from Primitive Methodist homes. It embraced lawyers, doctors, teachers, professors, a knight or two and a Member of Parliament. What a difference there would have been if all these men had been retained in the service of their church! Just now, when it is hard to find trained men to fill our pulpits and teach our higher classes, and when, for want of leaders, our young men drift away, the need of strong churches near the Universities ought to be obvious, and to neglect places like Cambridge would be a bad tactical blunder.

As to the past, it is not easy to tabulate results. To the Cambridge Circuit more people are indebted than can be enumerated here. Suffice it to say that in one of the chapels, Gipsy Smith, the famous evangelist, was converted and received his early training; that in another a gifted college tutor was led to take up Christian work; and that from a third our own ministry has been enriched by quite a number of men. Three of the professors at Hartley College graduated at Cambridge and attended our services. In this way the Circuit has contributed to Connexional and religious work generally. Who shall say what good it will do under worthier conditions in the days to come?

References

Christian Messenger 1912/362

No Comments

Add a comment about this page